While Jenni and I were aimlessly exploring a 19th-century town on Florida’s coast and finding our way to harmony with nature a couple of weeks ago, the BLS was busy releasing their latest CPI report. This US government report on the consumer price index was hotly anticipated as it’s often a key indicator for inflation. If you’re on the path to financial independence or already in the breezy transition to retiring early like us, inflation might be one of those trigger words sending chills up your spine.

In this post, I’m going to briefly write about how inflation affects your retirement spending, FIRE number, and why the 4% rule has got you covered.

But first, I want to clear up a confusing element to that tried-and-true “4% rule” that a friend sent me a question about recently. It ties into inflation and why the financial news media’s inflation scare tactics probably aren’t something you need to worry much about.

Confusion with Withdrawal Rates

A good friend of mine sent a note of congratulations recently as Jenni and I crossed the “double double comma club“. That’s right, we’ve got more than $2M in assets.

It’s a big milestone for us! Almost enough to convince me to indulge in one of these while we were taking a break from our hiking around the beach recently:

But alas, while the $4 or $5 for the cookie wouldn’t break our bank, it might just bust my waistline. And not unlike inflation, those extra calories sneak up on you and build on themselves over time.

My buddy followed his compliment with an aside saying we’re sitting pretty financially and can probably afford to loosen up on our spending. Looking at our FIRE budget from 2020, we spent a hair over $40K during the course of the year. Following the 4% rule, we would need only a bit over $1M ($40,862*25=$1,021,550) to continue our 2020 lifestyle in early retirement.

Reading we had nearly double that, it’s easy to see how it might make sense to loosen up and willingly spend more—if you so desired.

Two problems

But here’s where things get a little tricky in two ways.

- Jenni and I have our own unique income situation, as most folks do, that isn’t strictly “retired” or “working” which makes it a little difficult to decide when we’ve started drawing down our nest egg

- And relatedly, my buddy (and I’m sure many others, likely even some reading this) was a little confused about how much money you withdraw from your investments each year for spending

Let’s address the second issue since I think it’s important to clarify right away.

Defining your retirement spending baseline

When working with the 4% rule (whether you’re more conservative and use 3% or less risk-averse and use 5%), you define your spending baseline in the initial year of drawing down your assets.

What do I mean by this?

Let’s say you’ve saved up $1,000,000. In recent years you’ve spent $40,000 on average to support your lifestyle. You think you can maintain this lifestyle in the future and want to retire early. You decide to start the process of quitting your job by slowly finishing up projects, turning in notice to your employer months ahead of time, and wait until after a holiday break to have your party at the office and last day.

During those last months, you earned more money and your investments rose. You’ve got $1.1M to your name and you’re ready to make your first withdrawal in retirement to support the life you’ve built.

At this point, you could withdraw 4% as planned ($44,000) which would yield a bit more room for spending since you’ve saved more.

Alternatively, you could stick with your existing lifestyle of $40K/year and reduce your withdrawal rate for a little more security in your long-term retirement plan and likelihood for success. This would reduce your safe withdrawal rate (SWR) from 4% to about 3.6%.

And while life is all about choices, let’s assume you go with the former—you stick to 4% and decide to boost your annual spending to $44K. Maybe you want to squeeze in a few more international trips or take on an expensive hobby that didn’t fit within your previous budget. Whatever. You’ve bumped your spending by 10%.

A year passes and you’re happy as a clam enjoying retired life. It’s time to adjust your withdrawals and tally up your assets to see how things have gone. Let’s assume the market has had a fantastic year and your net worth is up a whopping 35% (not impossible, at the time of writing the S&P 500 is up almost 41% in the last 12 months!).

Here’s how this looks in your early retirement spreadsheet:

| Year | Start Balance ($) | Withdrawal ($) | Appreciation ($) | End Balance ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,100,000 | 44,000 | 385,000 | 1,441,000 |

| 2 | 1,441,000 | (X) | — | — |

The question I have for you is: how much do you withdraw from your assets and spend over the course of the coming year? What’s the answer to the “(X)” in the table above?

Pop quiz hotshot

Whip out your calculator and come up with the answer.

No really. I’ll wait.

Got it? Good.

What was your answer?

A) $44,000

B) $57,640

I hope you’re screaming at the screen “none of the above!” right now. And if not, you’re in good company. I think a lot of folks get this wrong. The truth is, you can’t answer this question, numerically at least, with the information I’ve given you.

If you answered “B) $57,640”, you’ve made a common mistake and recalculated your withdrawals based on current-year assets.

Even someone whom I know understands how the system works can confuse things with their phrasing:

As you can see, the 4% value is actually somewhat of a worst-case scenario in the 65 year period covered in the study. In many years, retirees could have spent 5% or more of their savings each year, and still ended up with a growing surplus.

Mr. Money Mustache (emphasis mine)

What MMM would have intended in this context is that “retirees could have spent 5% or more of their initial savings, adjusted for inflation, in each subsequent year, and still ended up with a growing surplus”. But of course that doesn’t roll off the tongue quite as well. And it’s still lacking clarity.

I’ll repeat what I wrote earlier: you define your spending baseline in the initial year of drawing down your assets.

The originator of the 4% rule and related Trinity Study does an even better job of explaining this:

The deleterious impact of the 1973-1974 period can be seen to reach back to retirement portfolios whose withdrawals begin many years earlier—as much as 20 or more years earlier! This is a powerful warning (particularly appropriate for recent retirees) not to increase their rate of withdrawal just because of a few good years early in retirement. Their “excess returns” early may be needed to balance off weaker returns later.

William P. Bengen, purveyor of the 4% rule.

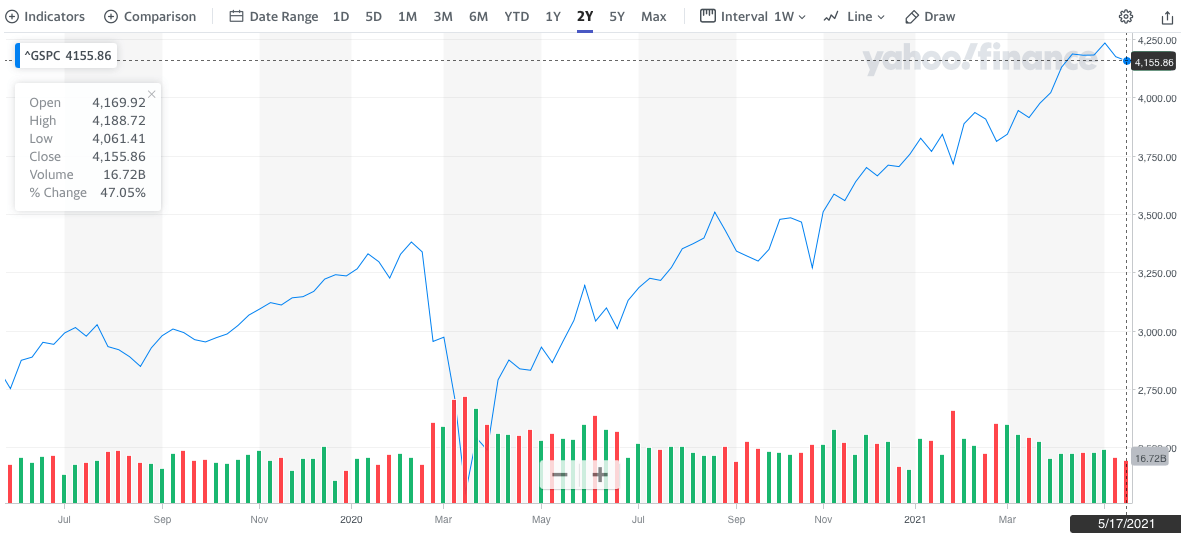

Mr. Bengen’s words are especially prescient in the context of the US stock market rise recently. Just look at this chart of the S&P 500 over the last two years!

Technically, you could have nearly any withdrawal rate and have a 100% chance of success if you simply recalculated your spending to each year’s asset base. But it would assume you could always keep your spending within the amount withdrawn. This would work if you have no minimum spending amount, like with our reader’s FIRE donation fund, but doesn’t when you have bare minimum spending amounts to stay alive as most humans do.

For example, if you decide to recalculate 4% withdrawal rates based on your $1,441,000 nest egg after a 35% market run-up and spend $57,640—you’d have to do the same if your assets were down 50% the next year. Suddenly your spending would be limited to $28,820!

The Trinity Study’s conclusions came from an assumption that people would continuously withdraw 4% (or 3%-5%) of their assets with adjustments for only one thing: inflation.

Which brings me the other answer: “A) $44,000”. While also not correct, it’s at least a little closer. Yeah, sorry, it was a bit of a trick question.

The closest answer you could give, that would be correct, is: “$44,000, adjusted for inflation”. The missing piece of information is inflation in the first year.

Let’s try again and I’ll give you all the information you need for the right answer:

| Year | Start Balance ($) | Withdrawal ($) | Appreciation ($) | End Balance ($) | Inflation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,100,000 | 44,000 | 385,000 | 1,441,000 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 1,441,000 | (X) | — | — |

Got that calculator out again? Good!

The correct answer is: $45,100 ($44,000 * 1.025).

In fact, whether year three looks like this:

| Year | Start Balance ($) | Withdrawal ($) | Appreciation ($) | End Balance ($) | Inflation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,100,000 | 44,000 | 385,000 | 1,441,000 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 1,441,000 | 45,100 | (478,000) | 917,900 | 3.8 |

| 3 | 917,900 | (X) |

—or like this:

| Year | Start Balance ($) | Withdrawal ($) | Appreciation ($) | End Balance ($) | Inflation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,100,000 | 44,000 | 385,000 | 1,441,000 | 2.5 |

| 2 | 1,441,000 | 45,100 | 123,000 | 1,518,900 | 3.8 |

| 3 | 1,518,900 | (X) |

—has no bearing on what the value of (X) is.

It’s a bit counterintuitive, but whether you’ve got just under $918K or $1.5M in year three of retirement, given equal inflation values, you’re supposed to withdraw $46,814 ($45,100 * 1.038).

But we’re not automatons

I’ve written “supposed to” because that’s how you’d match the Trinity Study and get the results you’d expect.

In reality, we’re human.

Hopefully, if the market is down 35% in a single year, you’d do your best to cut your spending as much as possible and try to earn a few thousand bucks from side gigs. Similarly, if you find your assets are way up—you’ve got more money than you thought you ever would—you’re human, and you might spend a little more than you intended. As long as it cuts both ways—you make adjustments in either case—you’ll probably be OK.

Technically, the whole point of the Trinity Study is that the underlying success rates account for the most extreme changes in investment markets, crushing inflation, and exceptional sequence of returns risk scenarios.

4% (Inflation-Adjusted)

The next time you see financial news headlines talking about rising inflation or even potential deflation, know that your early retirement plan and the 4% rule has got you covered. It’s part of the math already. Rest a little easier, take a deep breath.

You can tune in because of your interest in economic news and desire to understand how modern monetary policy works. But you needn’t melt into a clump of anxiety.

Unless of course, this time it’s different.

After all, we’re just working from historical data and as they say—past performance is no guarantee of future results!

Ha.

PS: If you’re still concerned and what to get into the nitty-gritty of managing your investments as it relates to potential inflation worries, Mr. Tako has some great advice in a recent post dealing with inflation.

So, how’d you do on my little withdrawal value calculation trick question? Let me know in the comments what you thought and if you’ve had similar confusion!

Epilogue

I touched on an element that was beyond the scope of this post that I’d like to address in the future. I wrote that:

“Jenni and I have our own unique income situation, as most folks do, that isn’t strictly ‘retired’ or ‘working’ which makes it a little difficult to decide when we’ve started drawing down our nest egg”.

For example, the “consulting” income that appears in our monthly budget updates is really just me drawing down part of our nest egg (my remaining business assets) which otherwise doesn’t appear as part of our net worth. While the business still earns some money, I suspect the assets will be fully converted to income within a few years. After all, if a normal full-time person works ~173 hours/month and I’ve only tracked ~24 hours/month, I’m about 86% retired you might say. That other 14% isn’t earning enough to supplant our spending—especially as lot of the work I do now is pro bono or business earnings flow through to folks I work with and mentor.

Similarly, Jenni’s income (“paycheck” in our budget updates) from her part-time work has been exceeded by our monthly spending on at least three occasions in the past year. We’re expecting to see her hours continue to decrease, especially later this summer.

I don’t think most FIRE folks are in cut-and-dry situations where all work-powered earnings suddenly stop and they fully convert to passive capital investment earnings to support their lifestyle. I think the RE part of FIRE is more gradual for many.

If you’re in a similar situation where you’re still earning some income but starting to reach the point where you’ll need to draw down your investments, I’d love to hear from you in the comments. When did you decide to mark the moment and set your 4% rule withdrawal baseline?

17 replies on “Why You Don’t Need To Worry About Inflation (and the 4% Rule)”

Nice write up on the 4% rule and inflation. It’s a good reminder that the original study and “rule” already account for volatility, inflation, etc. so no need to get swept up in the panic of the day. Add in the flexibility of earning side income and / or cutting expenses during extreme downturns and it becomes really unlikely that a portfolio draws down all the way to zero.

Thanks for writing it as “rule”—ha. I get tired of rewriting it as “rule of thumb” often and just fallback to “rule”, but it definitely should be thought of as a rule of thumb! It’s a place to start, not a hard and fast set of criteria.

In fact, arguably, you’ve already fallen off the 4% rule (of thumb) and the Trinity Study if you’ve diverged from the investment set that was core to the study (as in 50/50 stock/bond indexes for example).

The 4% rule (of thumb) is only as reliable as people can (or will) replicate, and most don’t. We’ve all got our own personal “expense ratios” exhibited by our silly human decisions like trying to time the market, dabbling in alternative investments, or holding too much cash.

But yes, as you said—the study does account for a lot of stuff I think people gloss over and think we’re “missing” within the FIRE community. Another is taxes, but frankly, I’ve always read it as if it was prescribing post tax numbers since everyone has different tax situations!

Phew… glad I passed the test! 🙂

This was an EXCELLENT write up on the 4% rule and how inflation plays into future withdrawals. To your point, I think there is confusion and hesitancy around whether 4% is still relevant today, particularly with regard to lower bonds yields and inflation.

I agree that 4% + inflation adjustments is still a relevant and safe withdrawal rate. It’s what we plan on using. Though I imagine we’ll also ease into retirement before taking the full baseline withdrawal. Even if our portfolio is larger by that point, we may still use our FIRE number to calculate the 4%, or maybe not. We’ll cross that bridge when we get there.

Haha, thanks Mrs. RFL! I hope you enjoyed it as a more interesting—dare I say fun—way to remind readers about the 4% rule basics. And yeah, bonds and low yields (interest rates in savings accounts, but also dividends by historic standards) cause people to shy away from some assets. But, those assets ARE what the Trinity Study …studied. So, technically, diverging from them is well…not part of the study (though I’m guessing some other numbers folks have patched up those gaps with different ratios or asset allocations and analyzed them like the Trinity Study).

If you throw a million at crypto and tell me you’ve got a couple million now next month, then ask if you should readjust your withdrawal rate for the new amount… I’ve got no idea what to tell you since your actions don’t have much in the way of historical data to work from!

Sounds like we’re in similar situations with a slow transition to FIRE. Keep me aprised!

Congrats on crossing that major milestone!

Well timed article. You break this concept of the 4% rule down perfectly.

In regards to inflation, I try to tune out the negative news for the most part, but all this inflation talk is really captivating. I’m eager to see if this recent surge is transitory (I truly hope it is). Reading about what happened in the ’70s and early 80’s is pretty scary. Luckily, there doesn’t look to be a recession to coincide with the recent rise in prices, like what happened back then. I’m feeling really grateful for refinancing recently. I think my parents had like an 18% interest rate on their first mortgage. Crazy. Anyway, it’s reassuring to read an article about the 4% rule being inflation adjusted

So far as all the inflation hubbub, it’s certainly pricked my ears up too. Don’t feel bad. 🙂 I think it’s more academically interesting than anything, but sure, that caveman brain is still there thinking “will there be enough food tomorrow?”.

As I mentioned in the epilogue, I’ve got a followup to this article that goes deeper on our personal financial situation and how we’re figuring out our FIRE number. I might touch on inflation a bit more there since it’s relevant. Some of my research for it lead me to a piece on Early Retirement Now. Specifically, I think you’ll find this chart interesting and perhaps reassuring:

The 4.2% April 2021 CPI rate isn’t too concerning in that context. At least, not yet.

Oh wow. Yeah that chart sure puts things into perspective. Talk about being able to see the forest from the trees…Thanks for including this.

I never actually understood the 4% rule beyond the first year of spending. Now I have a much clearer idea especially with the idea of inflation that’s added into the equation.

To be honest, I think I’ll figure out a way to decrease my expenses every year. My budget includes things that are fixed expenses so whatever I buy in year 1, I don’t have to buy for a solid 4 – 10 years after that.

Running out of money is on the list of my fears, however, of early retirement.

Hey David! Glad to hear the post might’ve been helpful to clear up any confusion. 🙂

Yeah, so far, our expenses haven’t really changed much since reaching FI back in 2018. I think they’ll go up a bit this year since we’re both paying for health insurance now, but they’ll probably stick with inflation in future years.

Indeed, one of the lower concerns I have related to FIRE is running out of money. Highly unlikely! Many other things are pressing as it relates to life which are more likely!

Hey Chris,

First time visitor here. Found your site on Reverse the Crush.

I picked the $57,640 for the trick question ?. This is a great write-up on the 4% rule. Similar to what David said earlier, I have only thought of the 4% safe withdrawal rate for the first year and just took the following years for granted with 4% withdrawal of current assets.

I have some more reading to do on this.

Alex! Nice to have you here, welcome!

And don’t feel bad. I’ve gotten a few private messages of others similarly confused. It’s easy to mix up!

If you play it out, you can see how it wouldn’t work too well if you’re always reevaluating the 4% basis. If you’ve got a 2008, 2001, etc recession and investments are down 30, 40, 50%—even mitigated with a bond balance—you’d likely wind up with too little investments (at a reevaluated 4%) to cover your original FIRE spending and not be able to pay your mortgage or other base bills.

Fortunately the base FIRE math accounts for this and even in these circumstances where you’re pulling out 6, 7, 8 percent of your basis when the market is down, future recovery makes up for it. At least, the vast majority of time. It’s those instances, with early market collapses, where the few percent chance of the math not working out with the 4% rule occur.

Hope you stick around and keep commenting Alex!

Funny you wrote this. What you calculated is EXACTLY how I interpreted the 4% rule – 4% initially, adjusted for inflation in perpetuity regardless of the current investment balance. I thought it was obvious!

Lots of folks seem to miss it! 🙂

This is the first time I’ve seen anyone cover what happens past the 1st year of retirement for the 4% rule. I feel like people think they can just calculate the 4% rule and then set it and forget it, but there are so many more factors that you pointed out. I also appreciate you highlighting the fact that we are human after all. Things don’t always go according to plan.

Thanks, FLA! Yep, with the 4% rule being such a core tenet of FIRE, I’m surprised how often the withdrawal mechanic is glossed over.

And indeed, if we were predictable, a whole lot of financial math would be much easier!

I’ll just live off of dividends in early retirement + any work/consulting I may do from time to time. Easy breezy (at least more so than the 4% rule is to me anyways).

As long as they’ll suit your needs it’ll certainly work! Dividends can be a little unpredictable with cuts depending on your portfolio, of course. But if you’re dividend-focused, you’re probably aware and account for that. I know that we’re living pretty well on the dividend rates from our broad indexes right now, which cover a significant portion of our annual expenses!